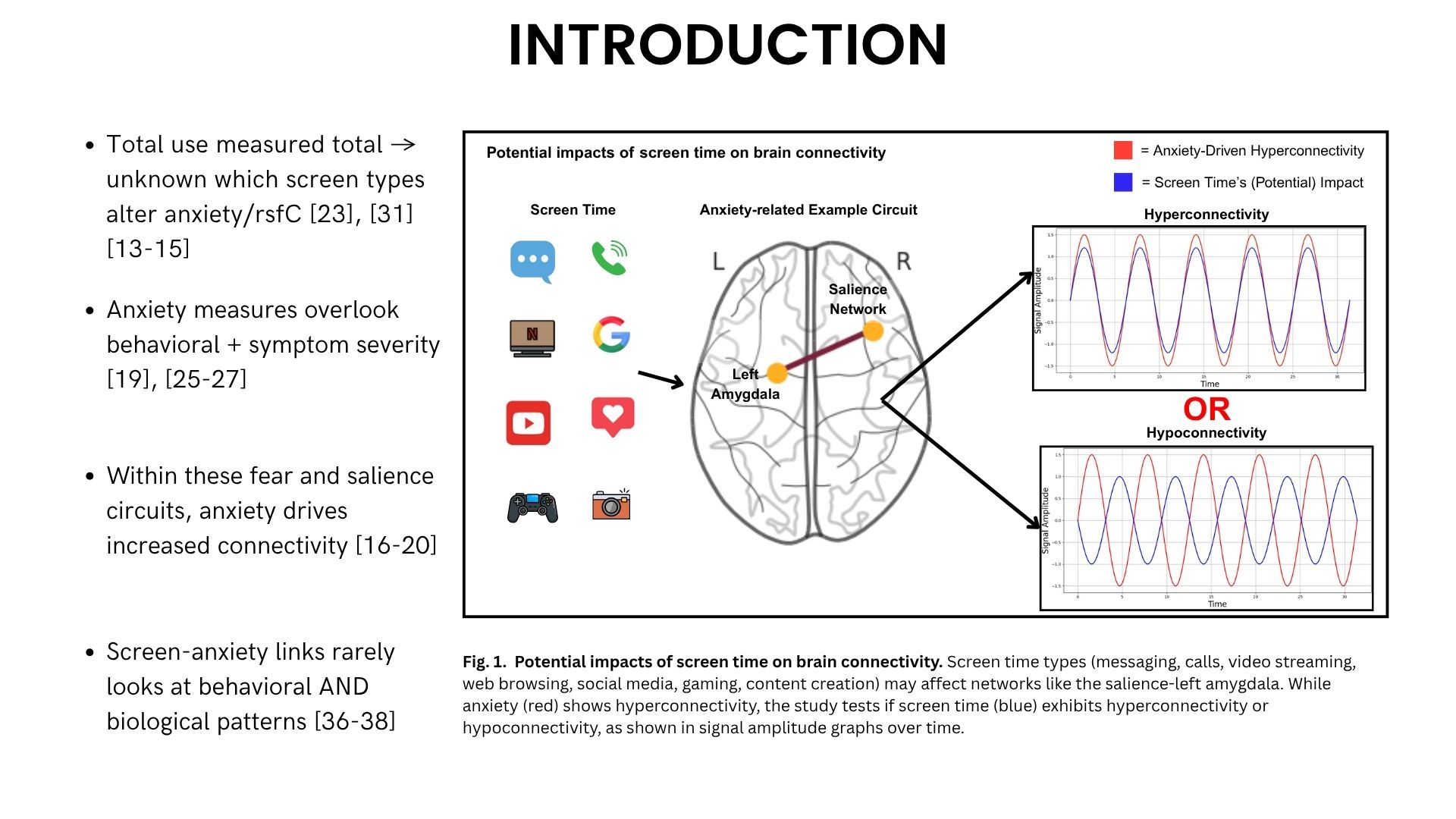

Adolescent anxiety has reached unprecedented levels. During the COVID-19 pandemic, anxiety symptoms affected 27% of adolescents [4-6], coinciding with dramatic increases in screen time as schools shifted to digital learning [1-3]. But here’s what most research misses: not all screen time is created equal. Scrolling social media, streaming videos, and playing games might affect the developing adolescent brain in fundamentally different ways.

I analyzed data from 7,675 adolescents to uncover which specific types of screen time predict anxiety—and how they alter the brain’s emotion-regulation circuits.

The Research Gap

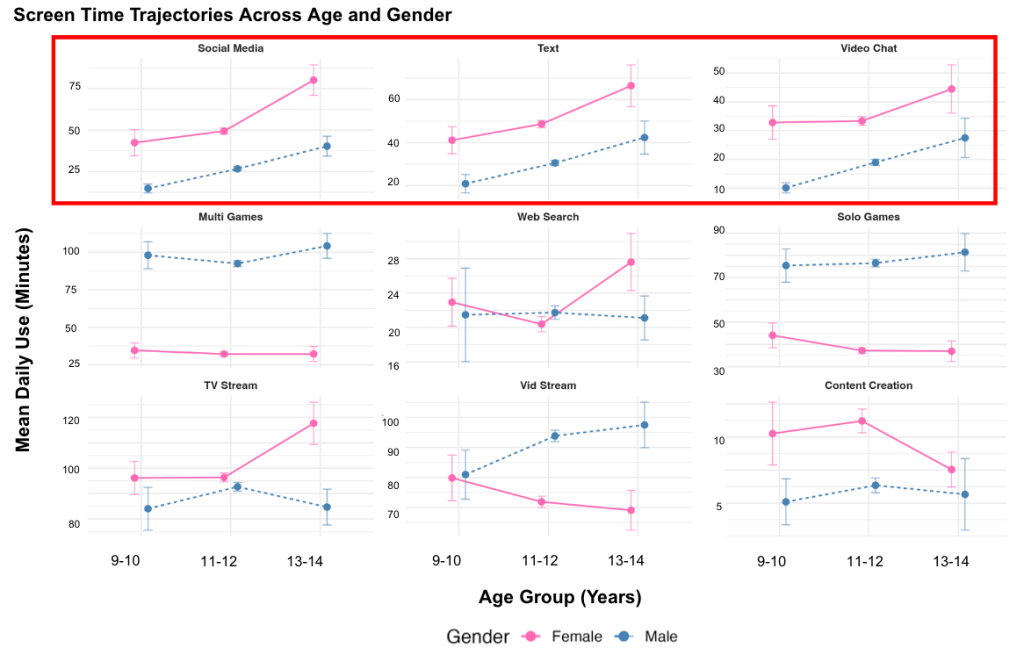

Most studies treat “screen time” as one monolithic behavior, measuring total daily hours without distinguishing between activities [23], [31]. But a teenager texting friends, watching Netflix, and gaming for an hour each might experience completely different psychological and neurological effects.

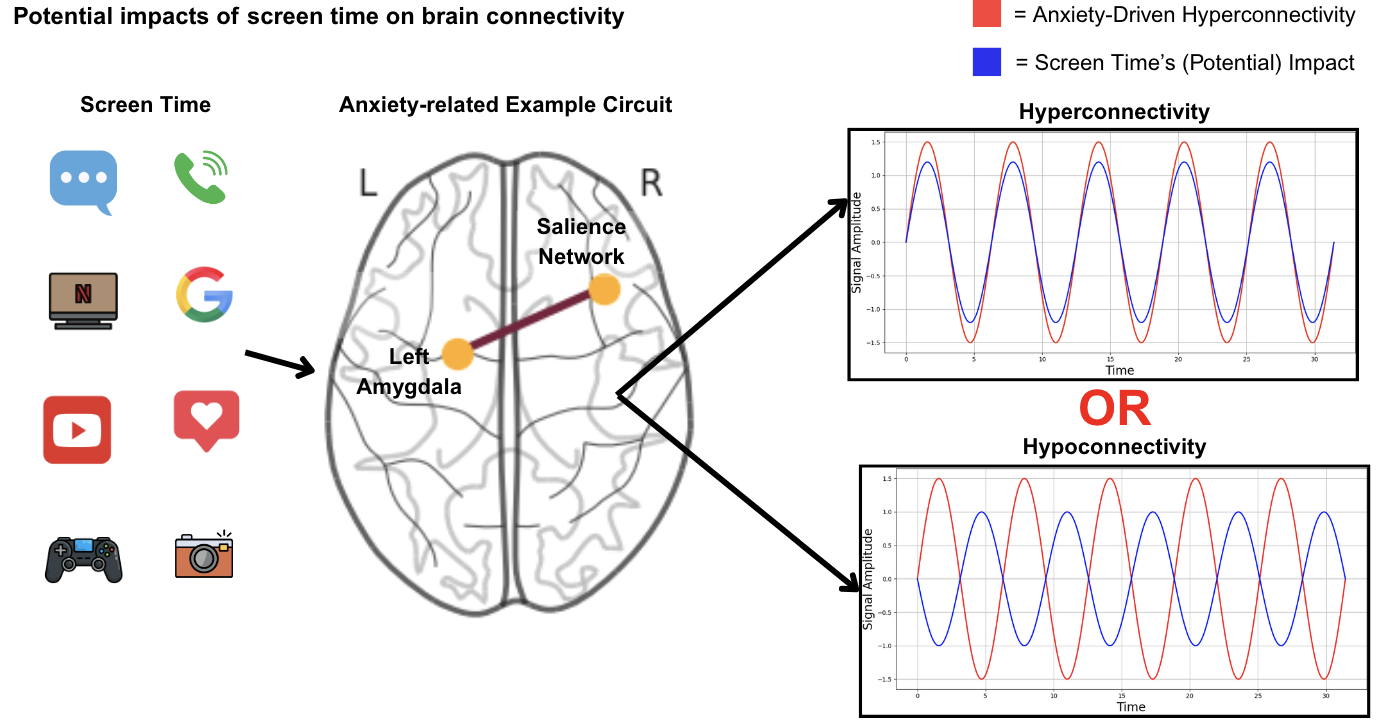

Additionally, research on adolescent anxiety typically focuses on behavioral symptoms while overlooking the brain mechanisms underlying these symptoms [19], [25-27]. Adolescence represents a critical window of brain development when neural circuits supporting emotion regulation are especially vulnerable to environmental influences [7-9], allowing long-term functional brain changes to be shaped by screen time [10-12].

What I Investigated

Using the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study—the largest long-term study of brain development in the United States—I examined:

- How do different types of screen time predict anxiety symptoms?

- Which brain circuits show altered connectivity in anxious adolescents?

- Does screen time strengthen or weaken these anxiety-related brain networks?

- Do different screen types have opposing effects on the brain?

Methods

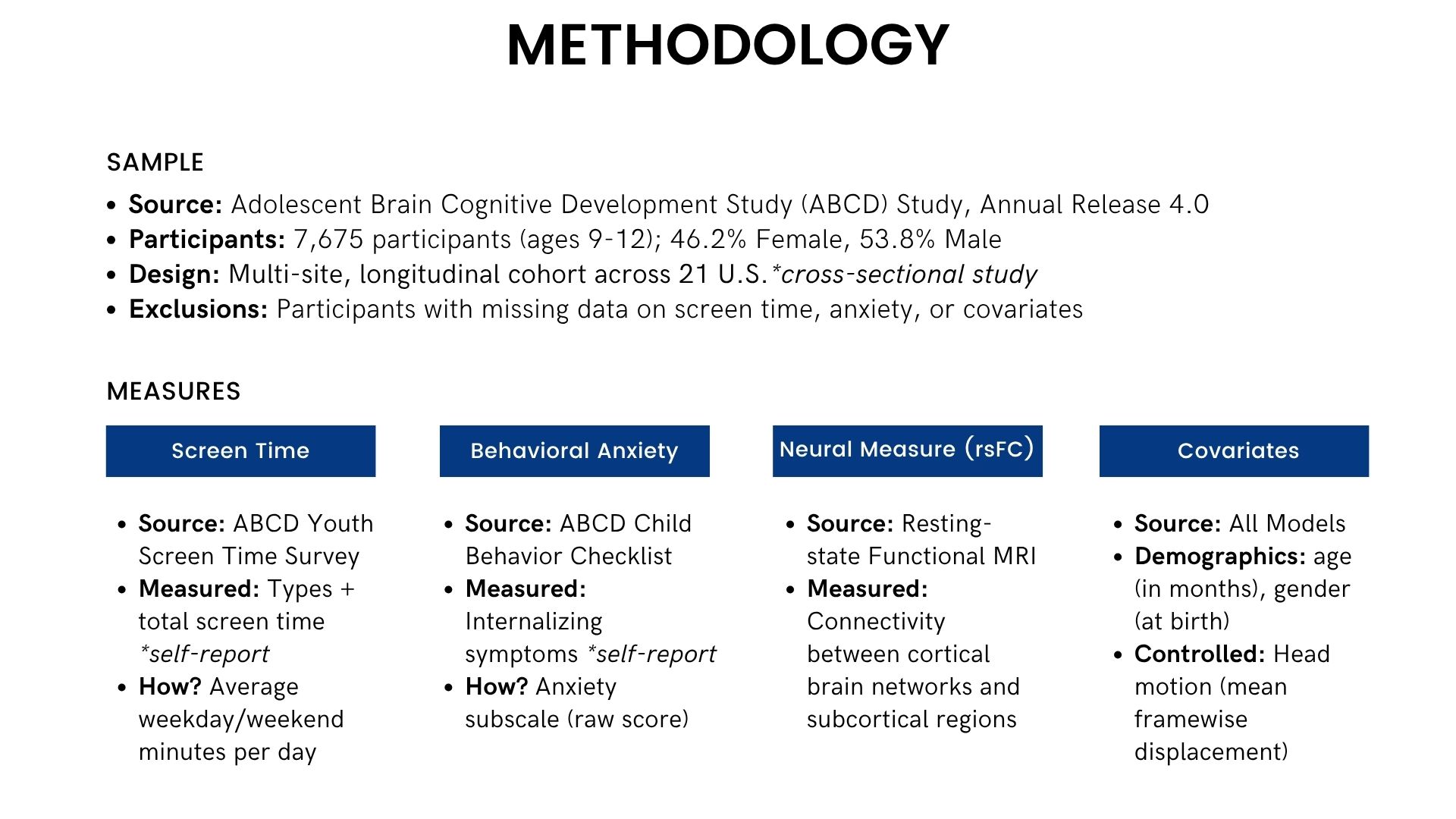

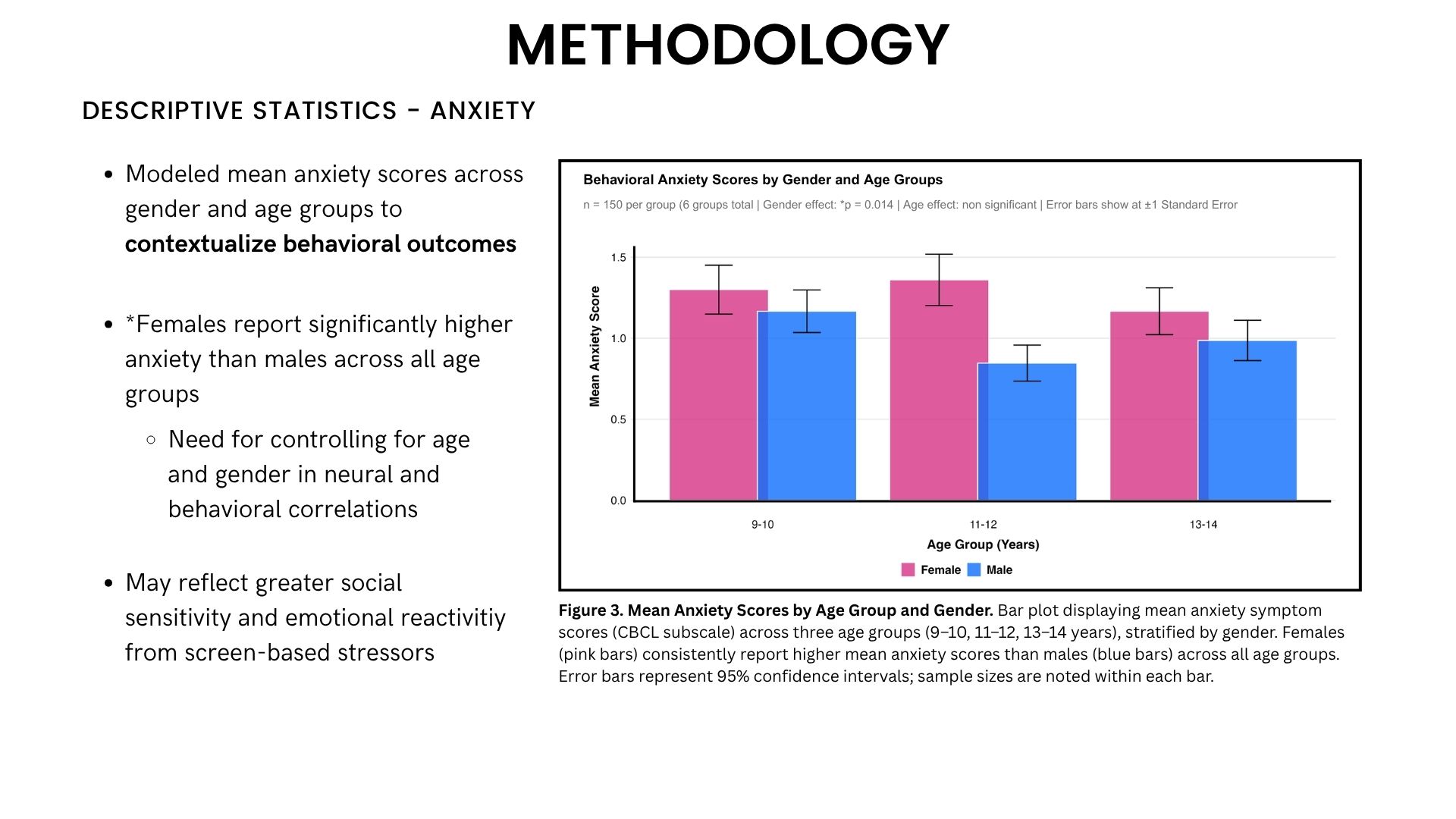

Sample: 7,675 adolescents aged 9-12 from 21 sites across the U.S.

Measures:

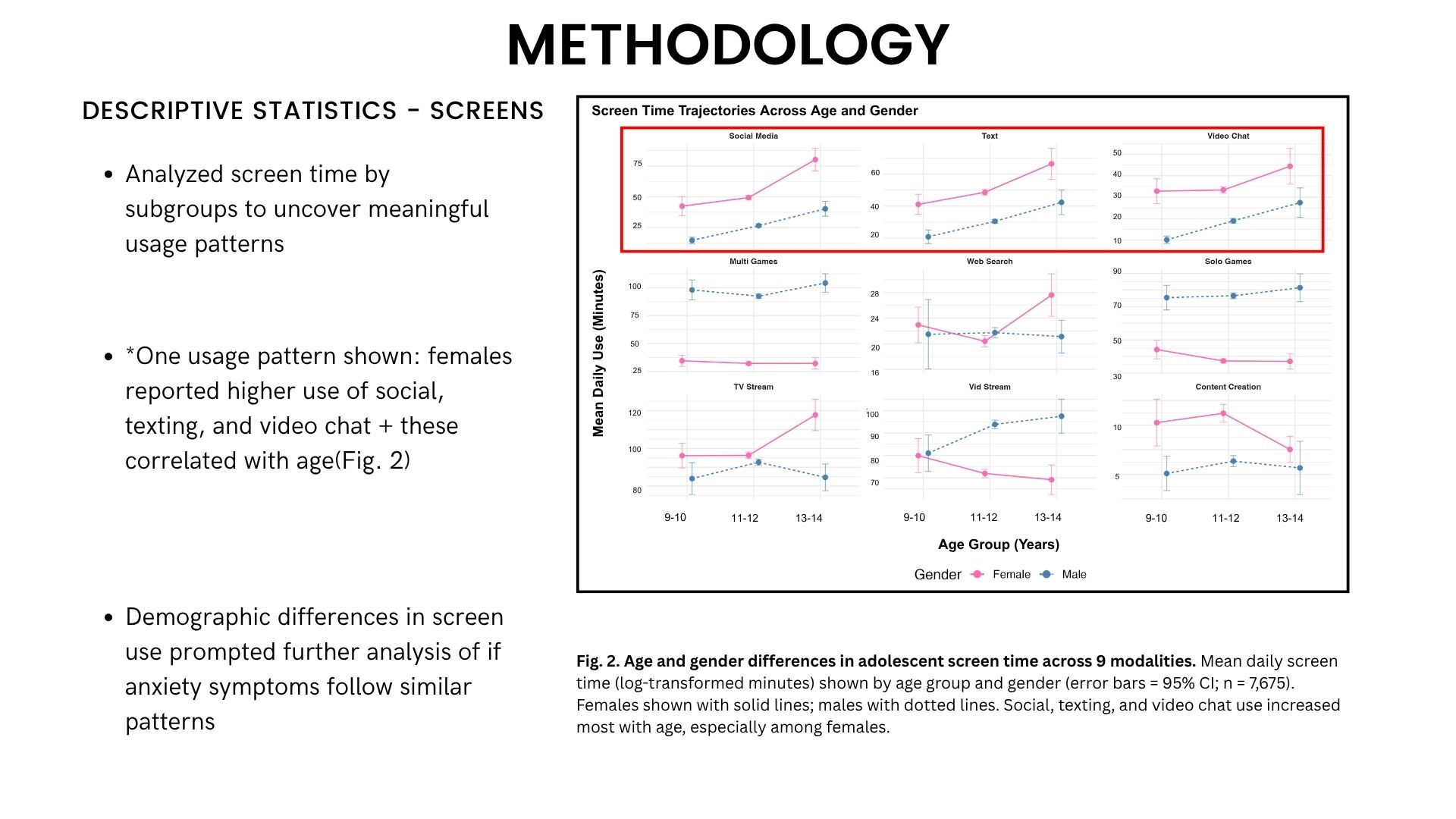

- Screen Time: Self-reported average daily minutes across 9 activities (social media, texting, video chat, video streaming, gaming, web search, content creation)

- Anxiety: Child Behavior Checklist internalizing symptoms subscale

- Brain Connectivity: Resting-state functional MRI measuring connectivity between 259 brain circuits involved in emotion regulation, threat detection, and cognitive control

Analyses: Linear regression models testing whether screen types predicted anxiety, and whether they altered the same brain circuits that anxiety affects. All results were corrected for multiple comparisons using False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction.

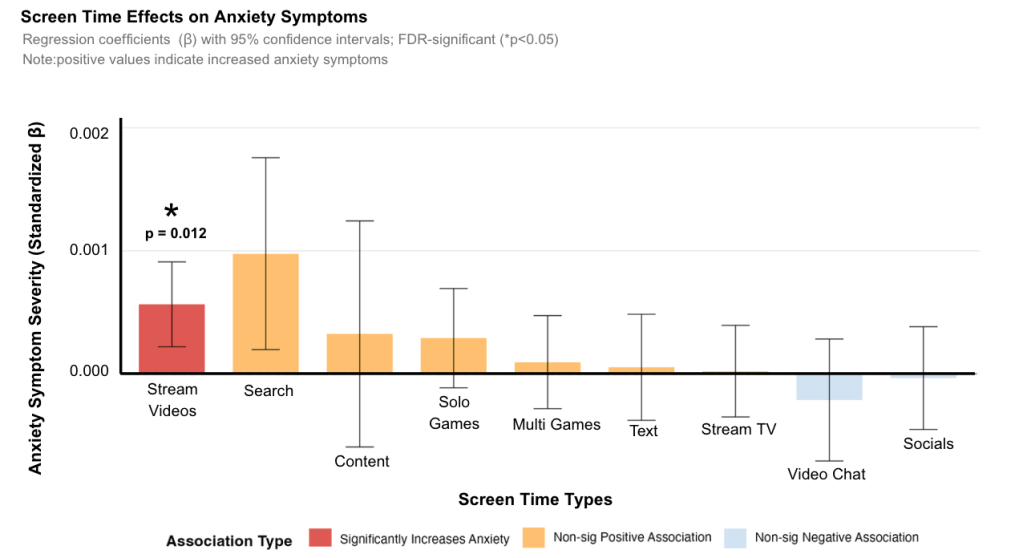

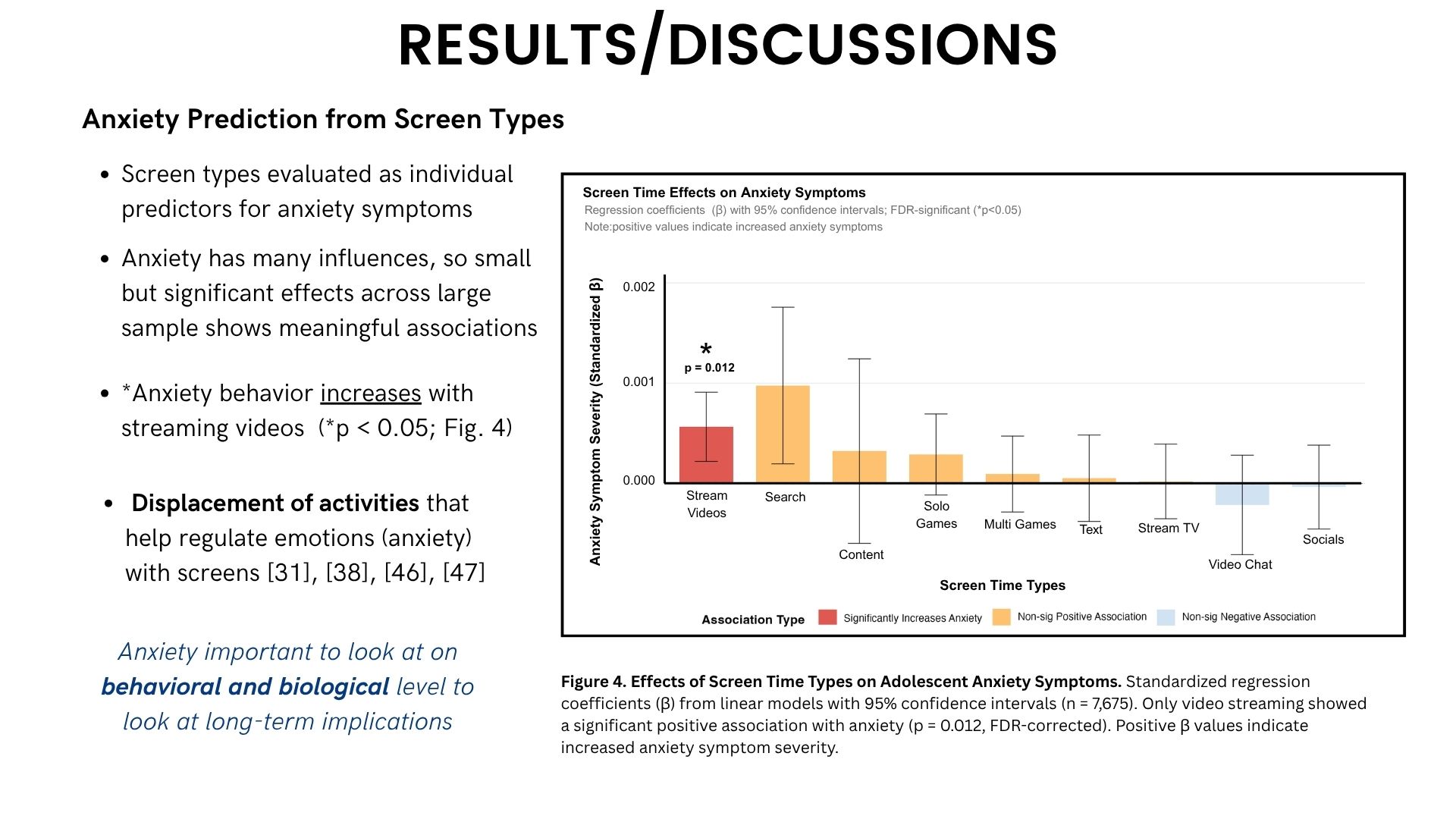

Finding #1: Only Video Streaming Predicts Increased Anxiety

When I tested each screen type individually, only one showed a significant relationship with anxiety symptoms: video streaming (β=0.001, p=0.012).

Social media, gaming, texting, and other activities showed no significant associations with anxiety in this sample. This finding challenges the common narrative that social media is the primary digital culprit in adolescent mental health.

Finding #2: Anxiety Strengthens Specific Brain Circuits

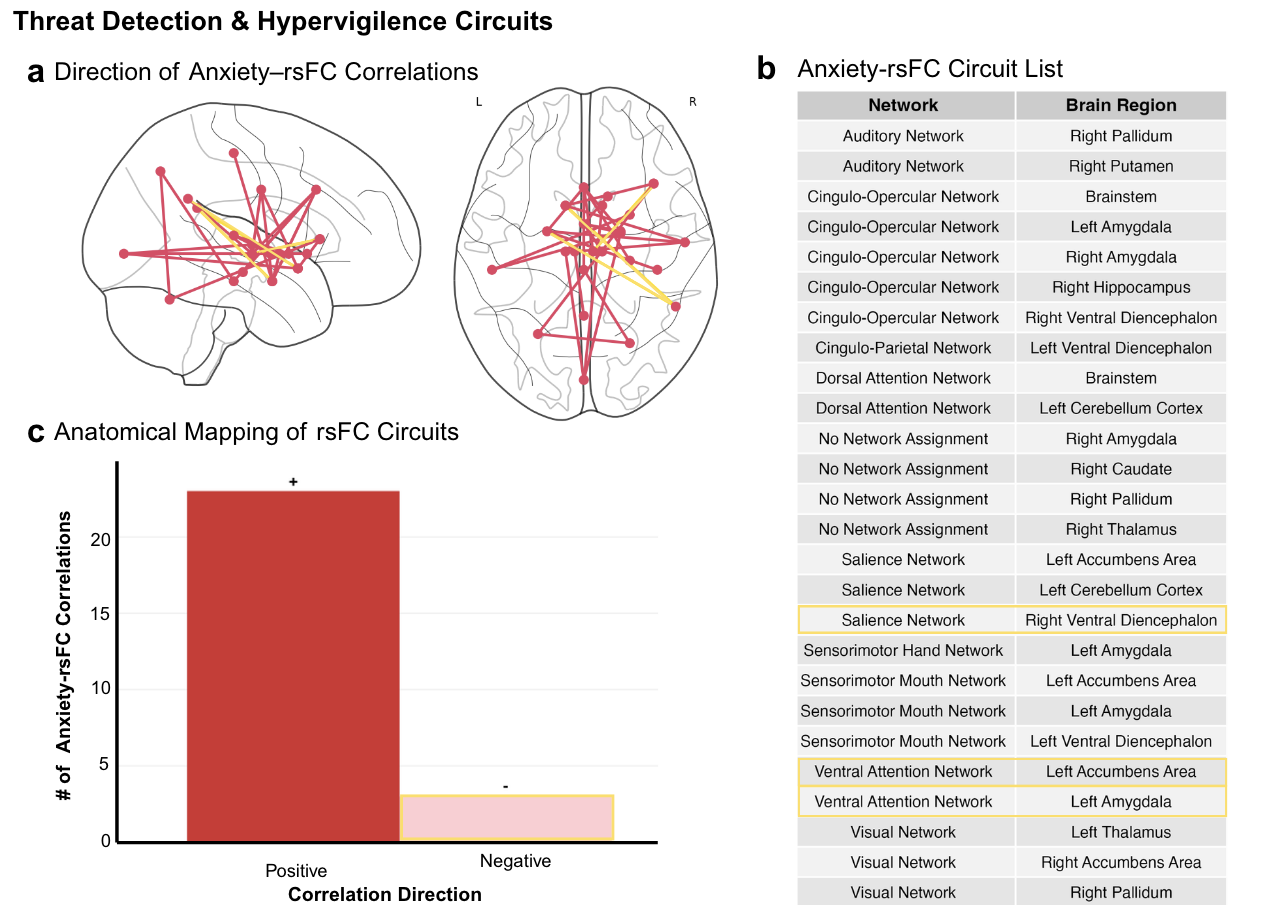

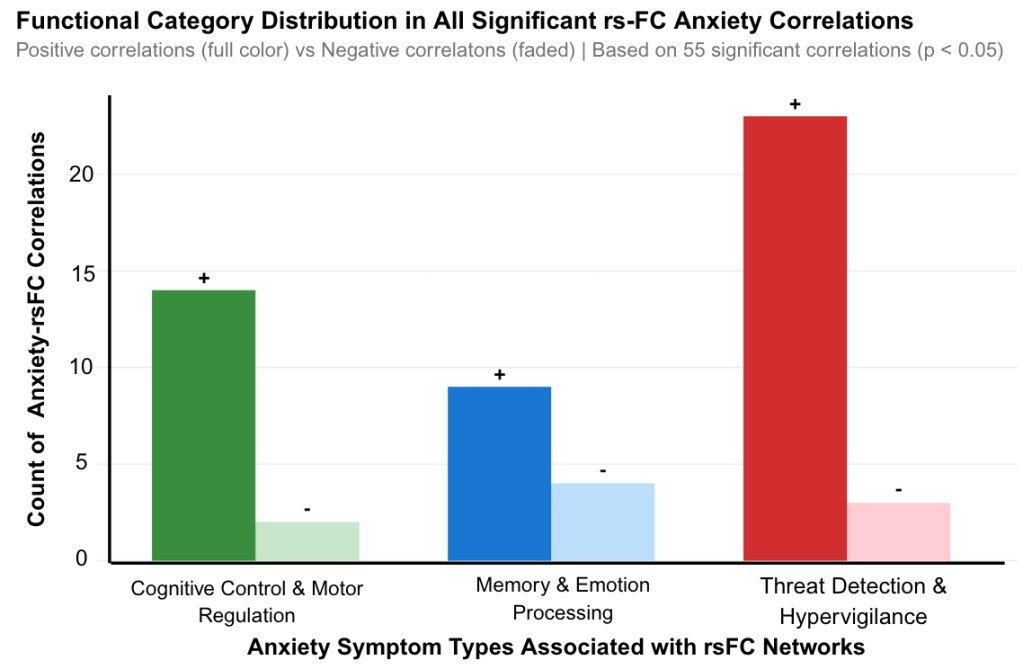

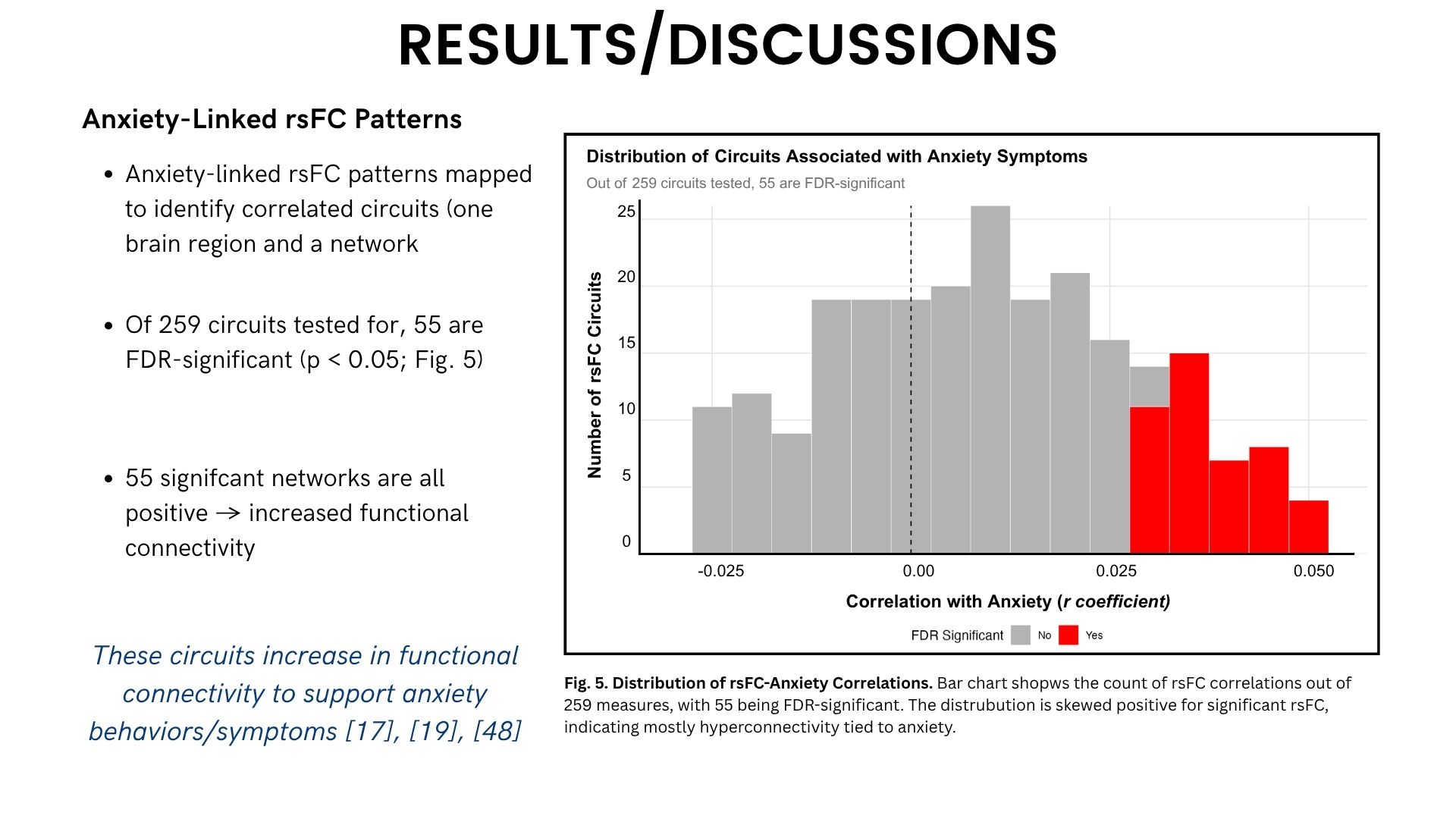

I identified 55 brain circuits (out of 259 tested) that showed significantly increased connectivity in adolescents with higher anxiety (p<0.05, FDR-corrected).

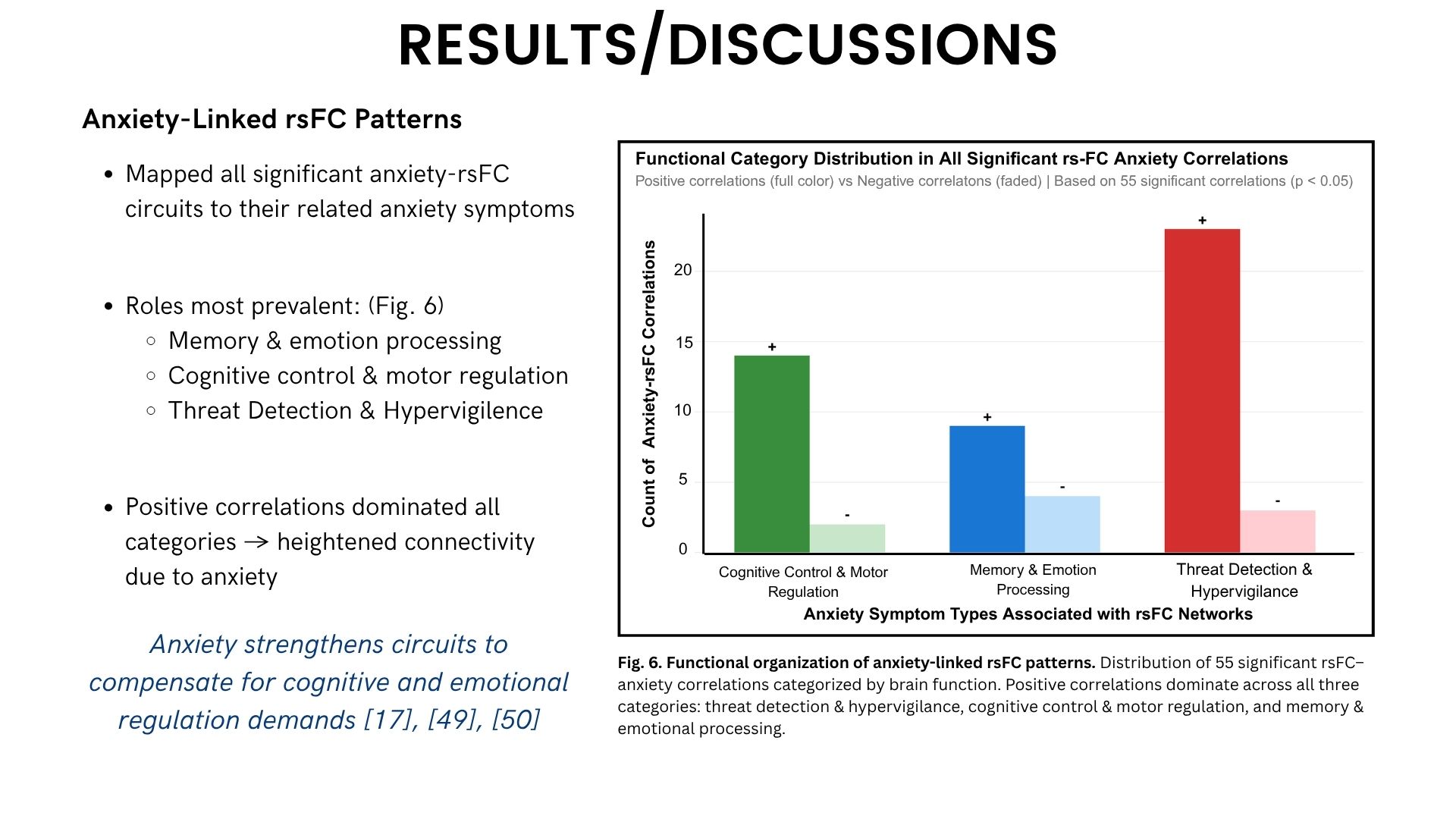

These circuits were organized into three functional categories:

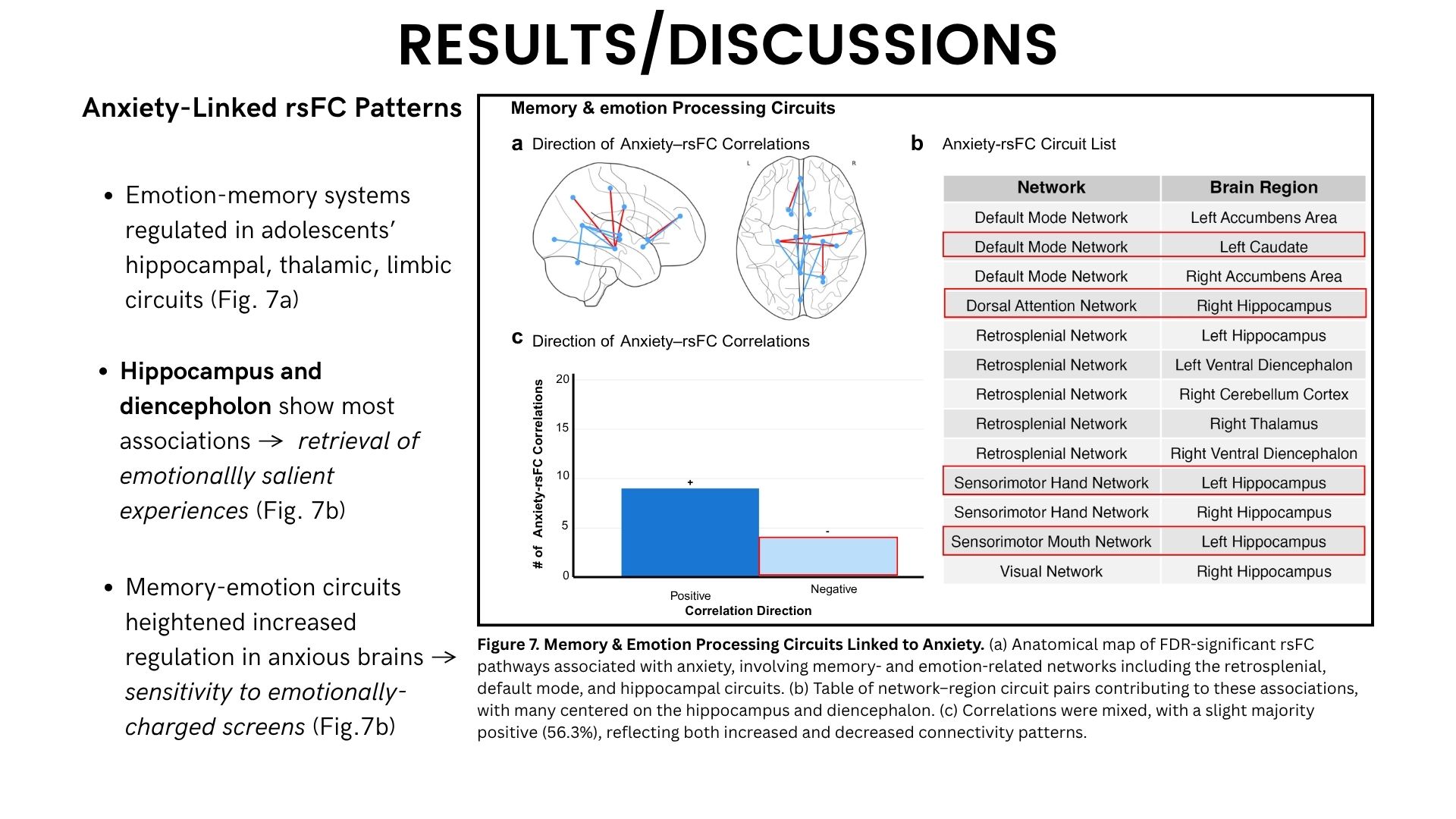

Memory & Emotion Processing: Circuits involving the hippocampus and diencephalon (thalamus) showed the strongest associations. These regions help retrieve emotionally charged memories and process sensory information related to threat [17], [49-50].

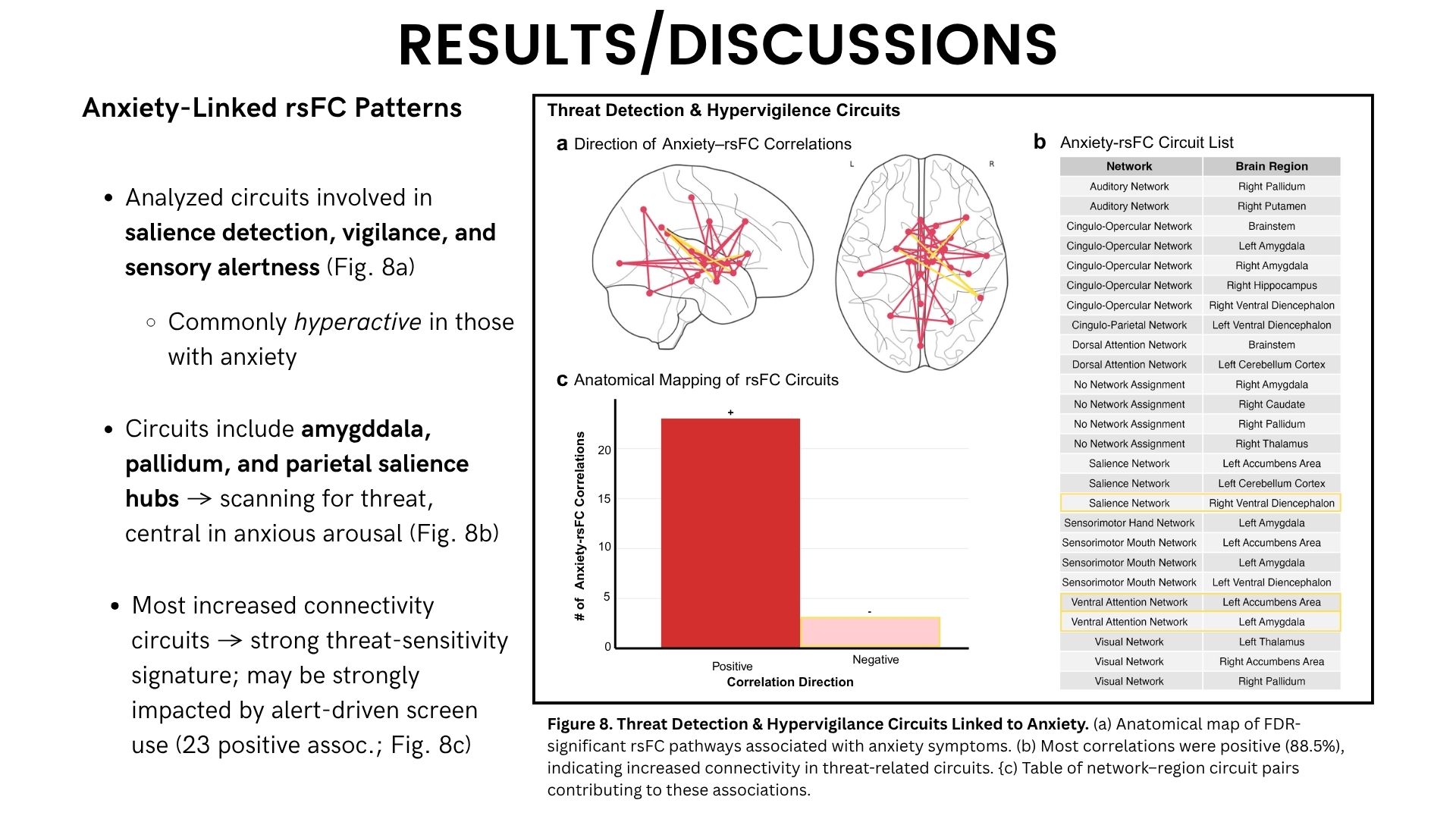

Threat Detection & Hypervigilance: Networks connecting the amygdala, pallidum, and salience hubs showed increased connectivity. These are the brain’s “alarm systems” that scan for potential danger [16-20].

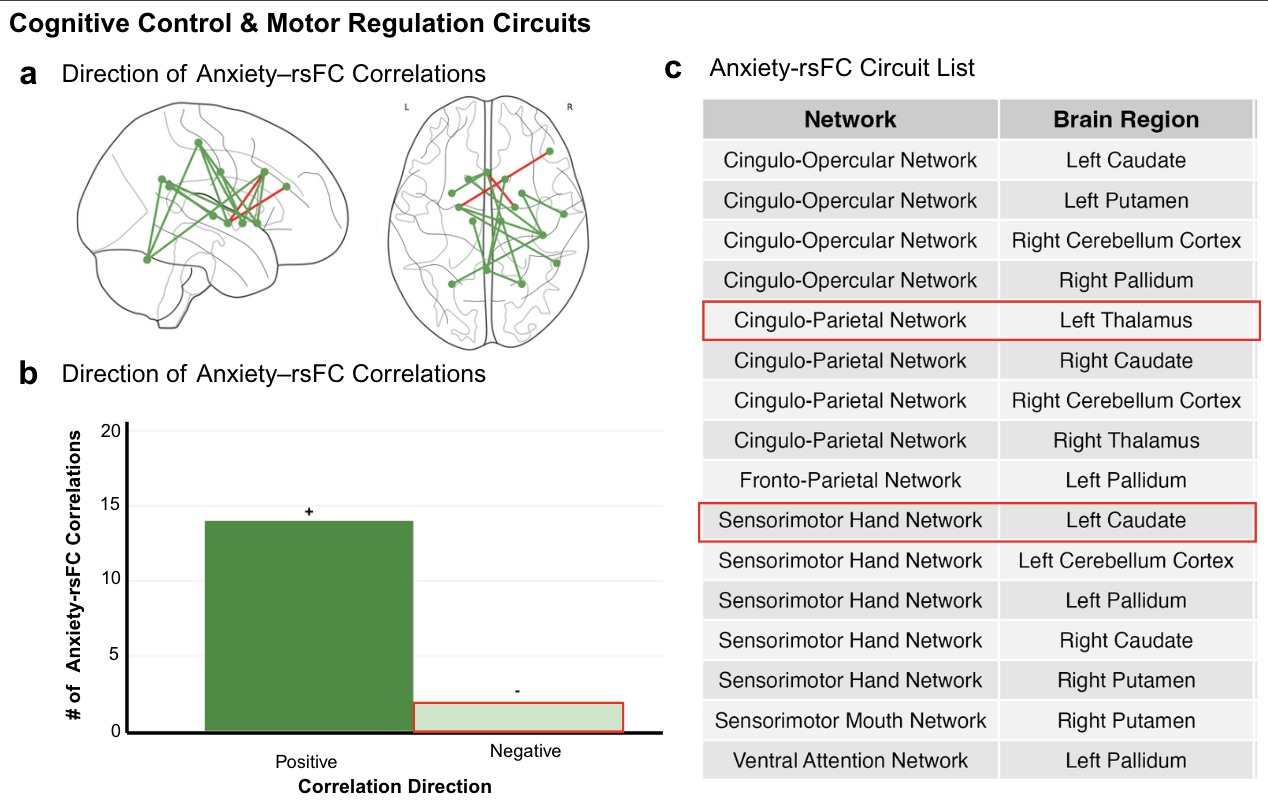

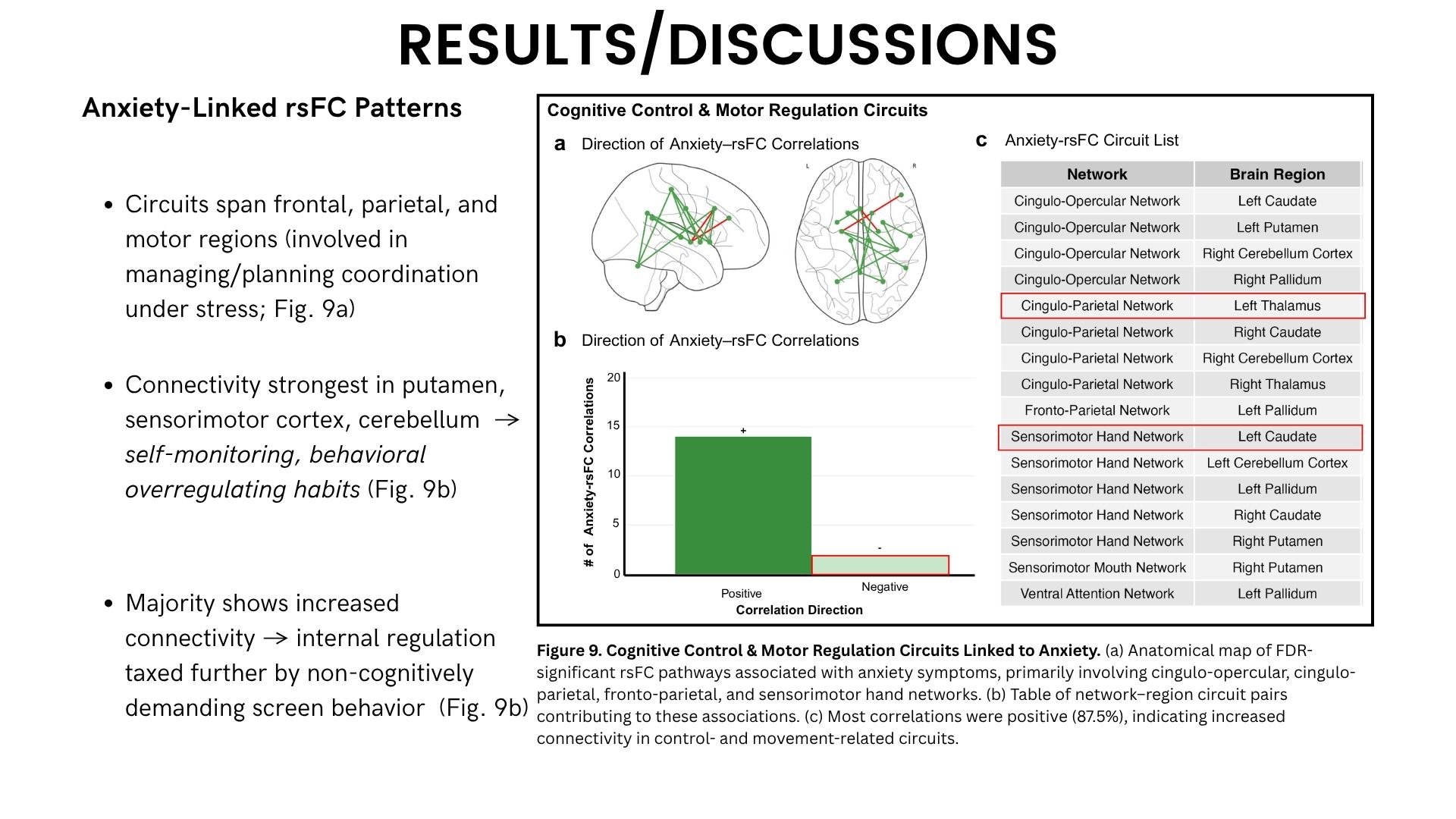

Cognitive Control & Motor Regulation: Frontal-parietal circuits involving the putamen, sensorimotor cortex, and cerebellum showed heightened connectivity, suggesting anxious adolescents’ brains work harder to regulate behavior and manage stress [17], [49], [50].

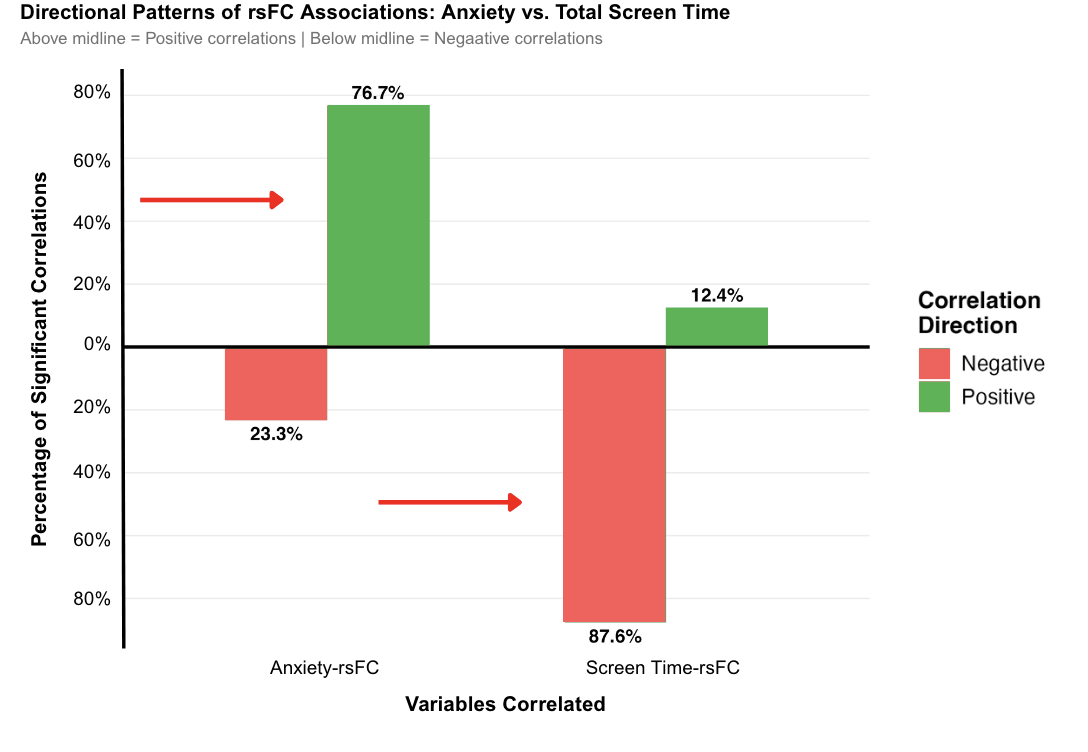

All 55 circuits showed positive correlations—meaning anxiety was associated with increased connectivity. This likely represents the brain’s compensatory mechanism: strengthening emotion-regulation networks to manage anxious feelings.

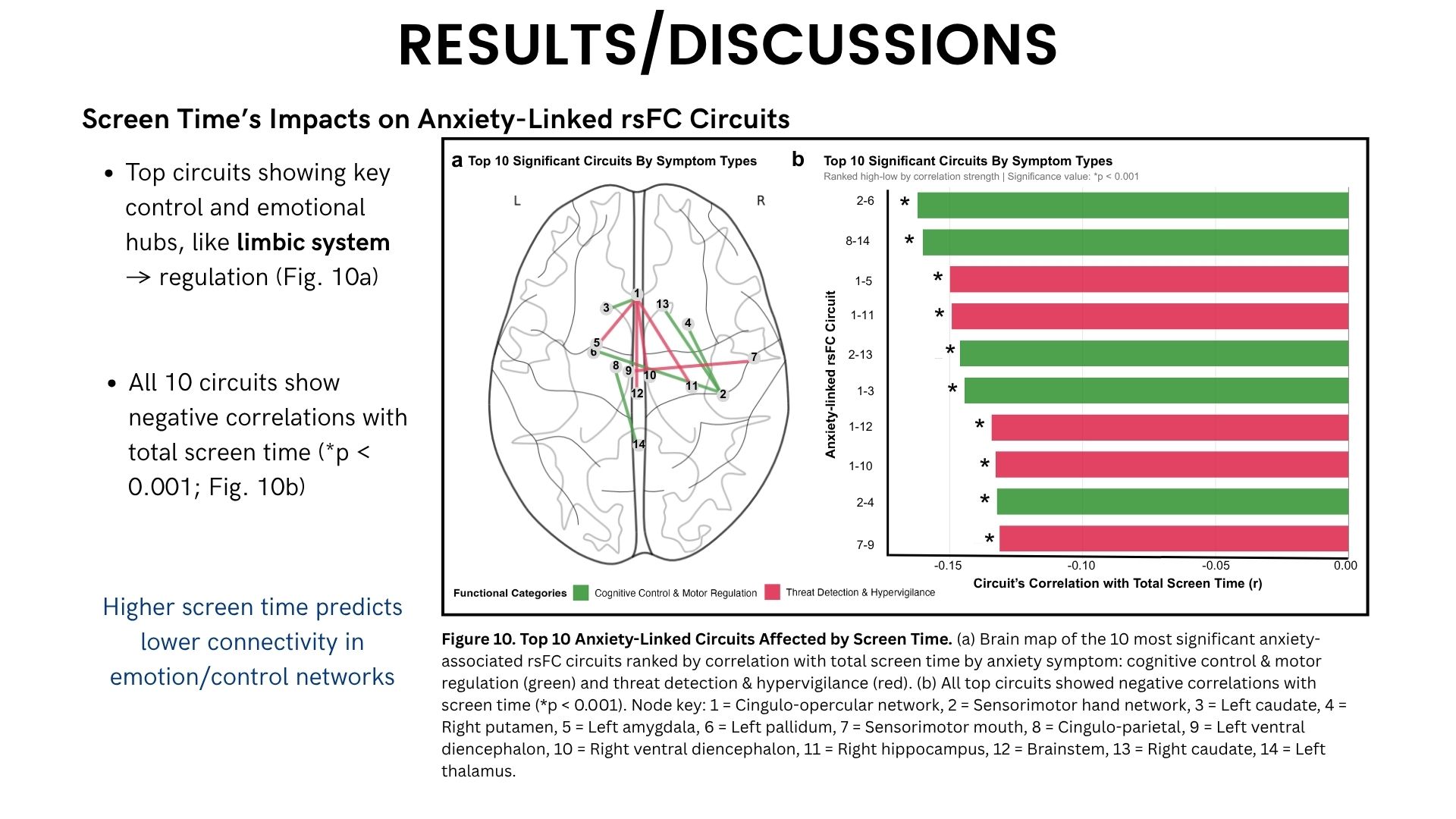

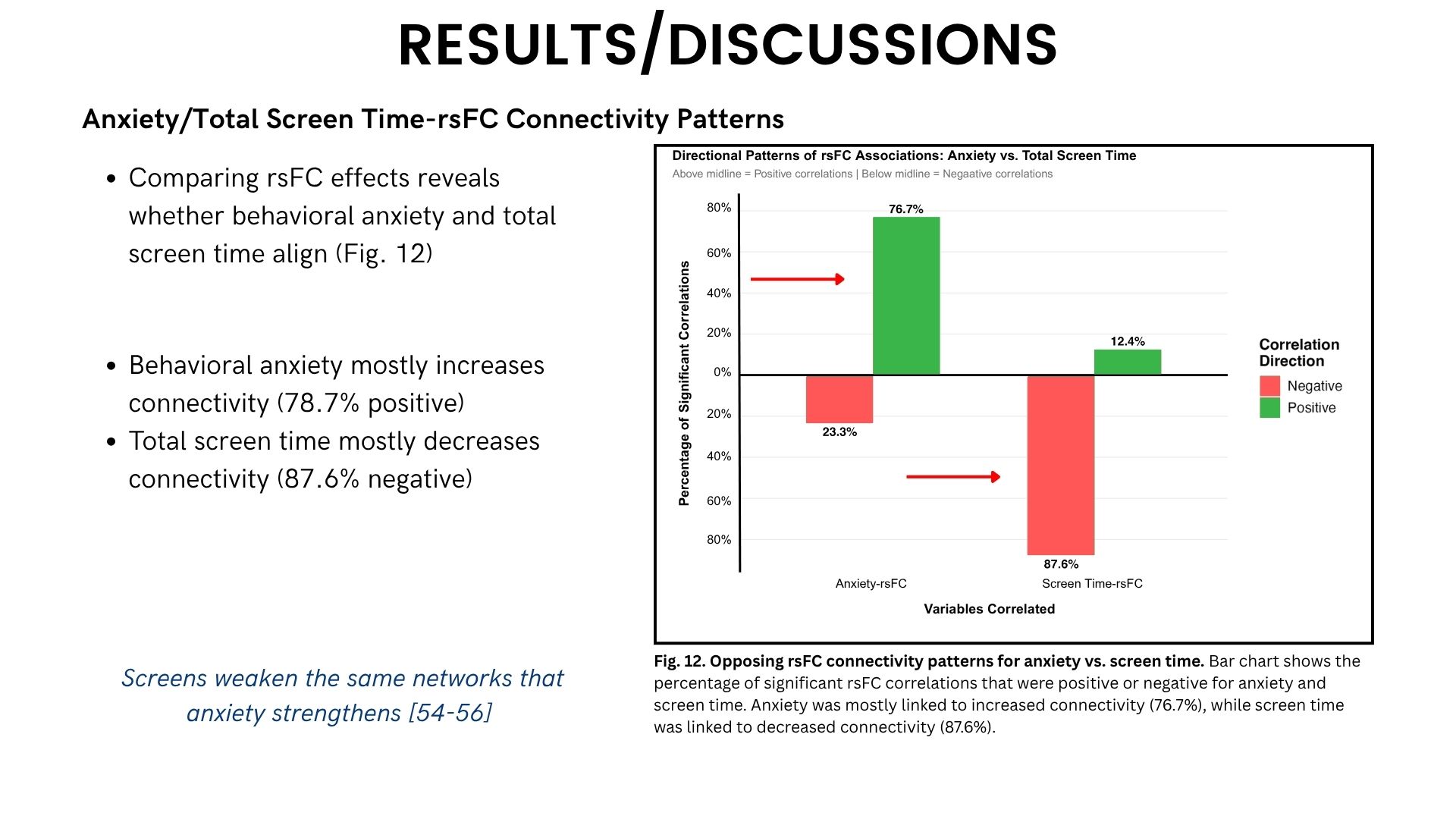

Finding #3: Screen Time Weakens the Same Circuits Anxiety Strengthens

Here’s where it gets interesting.

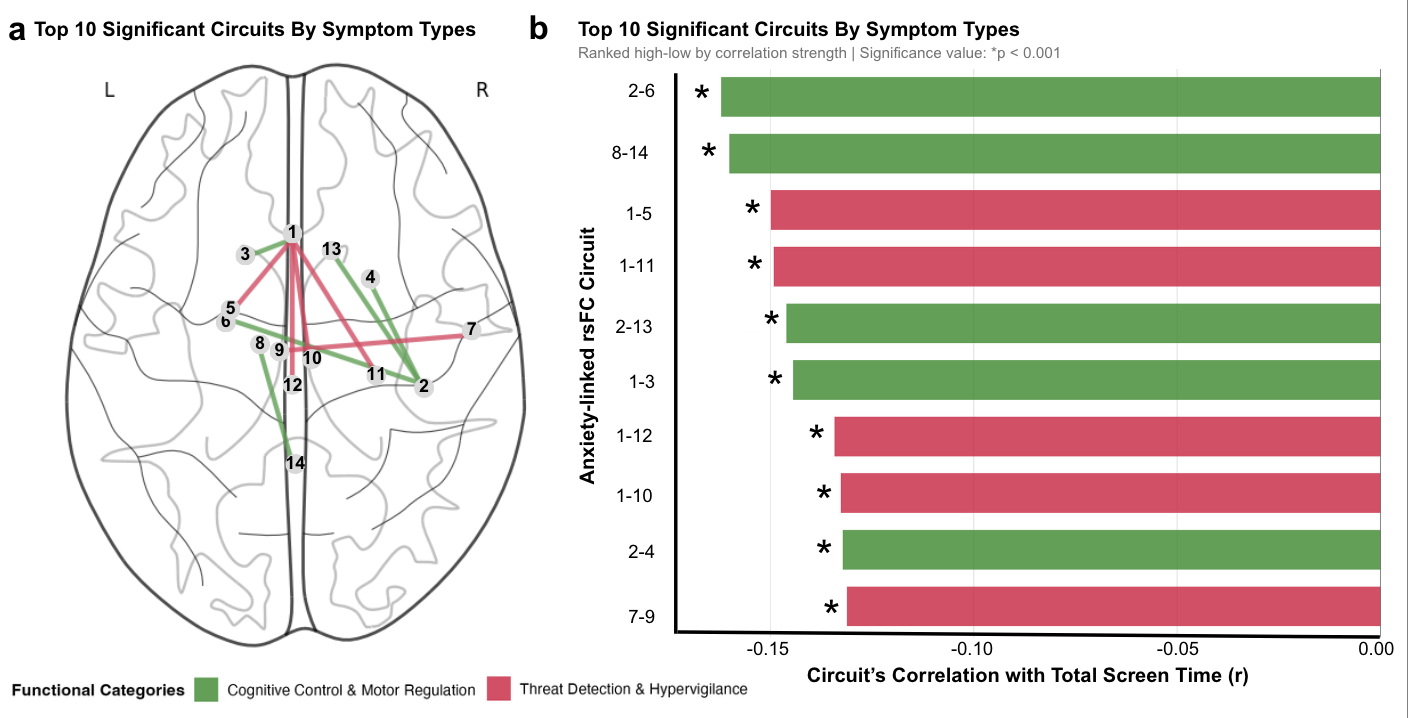

When I examined how total screen time related to these same 55 anxiety-linked circuits, I found the opposite pattern: 78.4% of screen time associations showed decreased connectivity [54-56].

The circuits most strongly linked to anxiety—including key limbic system hubs like the amygdala, hippocampus, pallidum, and thalamus—all showed significant reductions in connectivity with higher screen time (p<0.001).

This opposing directionality suggests that screen time doesn’t directly cause anxiety through the same neural pathways that support anxious symptoms. Instead, excessive screen use may weaken the brain’s compensatory emotion-regulation mechanisms [31], [38], [46-47], potentially leaving adolescents more vulnerable to anxiety over time.

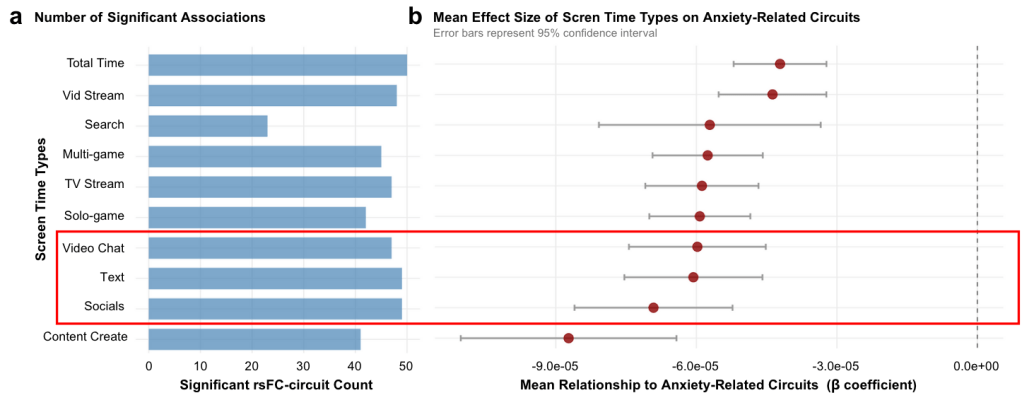

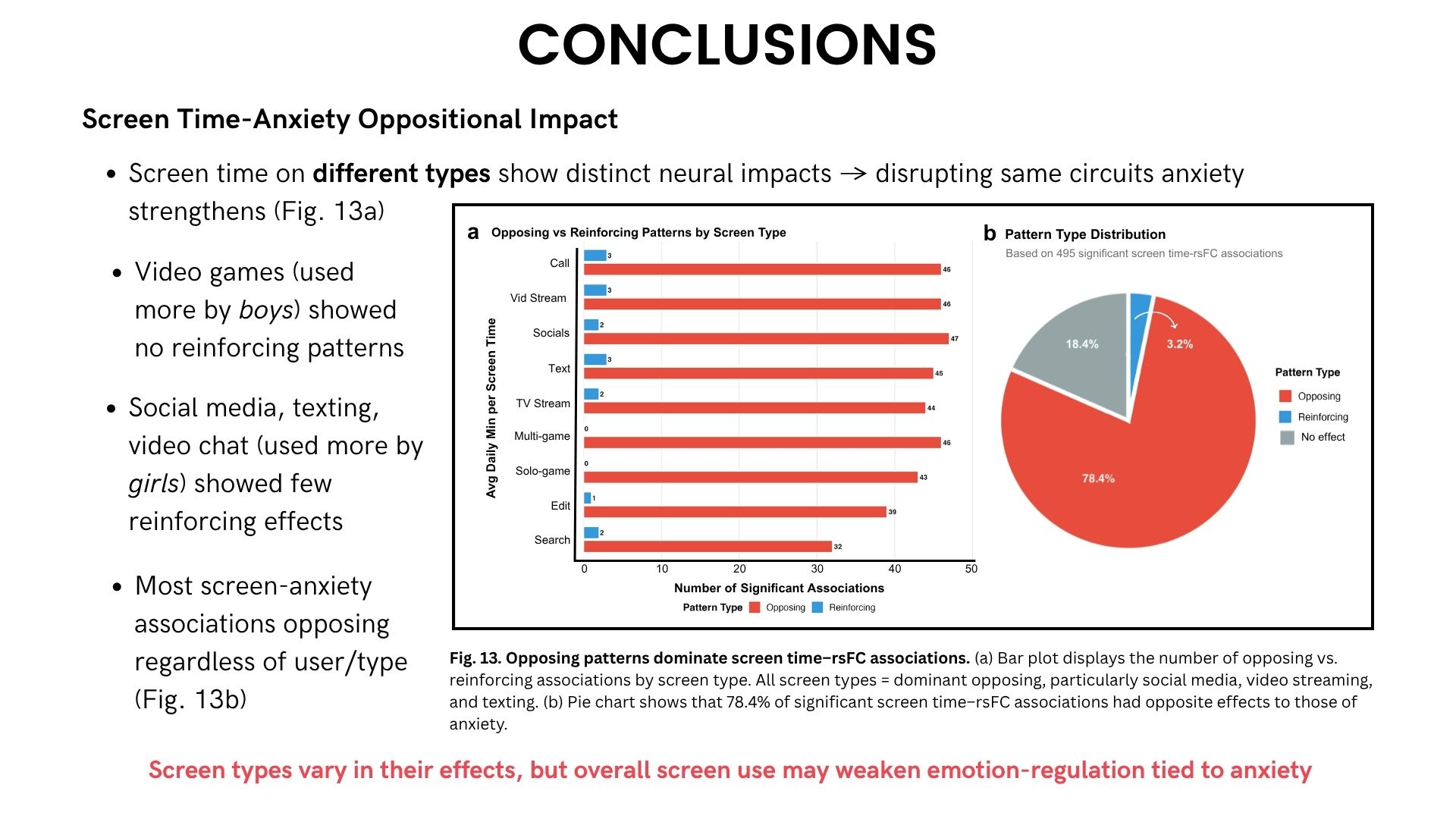

Finding #4: Different Screen Types, Different Brain Effects

Not all screen time weakened brain connectivity equally. When I mapped individual screen types onto anxiety-related circuits:

- Social communication screens (social media, texting, video chat) showed the strongest reductions in connectivity [51-53]

- Total screen time showed widespread decreases across all circuit types

- Brain connectivity decreased most dramatically in emotion-regulation and cognitive control networks

These findings reveal a critical insight: while anxiety strengthens brain circuits supporting vigilance and emotional processing, screen time weakens them.

Interestingly, while video streaming was the only screen type behaviorally predicting anxiety, social screens showed the strongest neural effects. This dissociation suggests behavioral symptoms and brain changes may operate on different timescales—neural alterations might precede observable anxiety symptoms [36-38].

What This Means

For parents and educators: Not all screen time affects adolescents equally. Video streaming appears most closely linked to anxiety symptoms, while social communication screens show the strongest brain connectivity reductions.

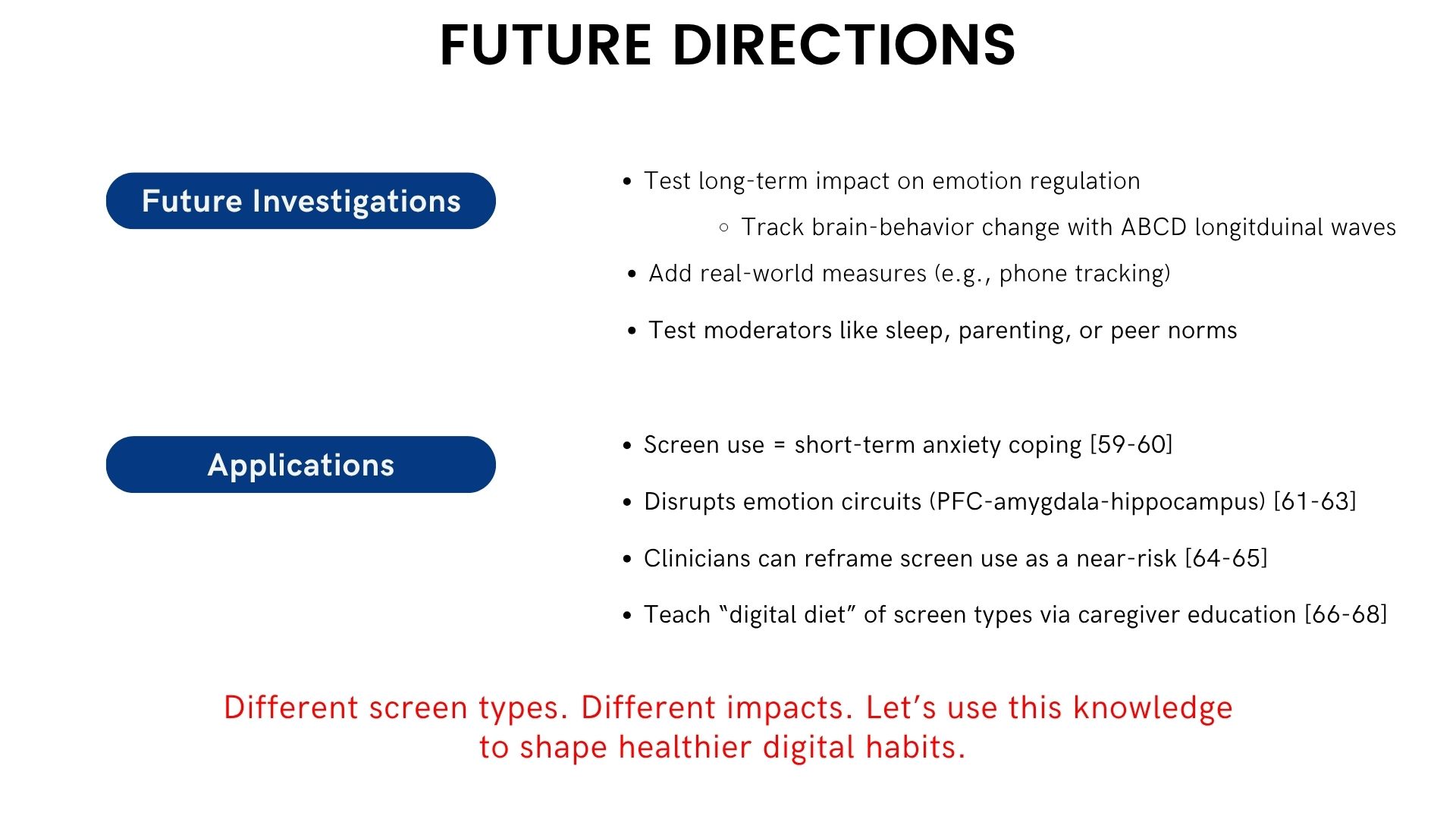

For researchers: Future studies should distinguish between screen types rather than measuring only total use [23], [31]. Longitudinal research is needed to determine whether connectivity reductions predict long-term mental health outcomes.

For adolescents: Screen time may interfere with the brain’s natural ability to regulate emotions during a critical developmental window [7-9], [10-12]. Being mindful of how you use screens—not just how much—matters for mental health.

Limitations & Future Directions

This study used cross-sectional data, meaning I captured a single snapshot in time. I can’t determine whether screen time causes these brain changes or whether adolescents with certain brain patterns are drawn to more screen use.

Future research should track brain-behavior changes across multiple timepoints using ABCD’s longitudinal data, incorporate real-world measures like smartphone tracking, test potential moderators like sleep quality and parenting practices, and examine whether reducing specific screen types can protect vulnerable adolescents.

Full presentation here:

About This Research: This project was conducted through the iResearch Institute Advanced STEM Research Program under the mentorship of Dr. Analia Marzoratti. Data come from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, Annual Release 4.0.

References

[1] E. J. Choi, G. K. C. Kong, and E. G. Duerson, “Screen time in children and youth during the pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Global Pediatrics, vol. 8, p. 100080, 2023.

[2] J. M. Nagata et al., “Screen time from pre-pandemic to 2022 in US adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the adolescent brain cognitive development study,” JAMA Pediatrics, Sep. 2024.

[3] R. Marius et al., “Impact of elevated screen time on school-age adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analytical study,” Cureus, vol. 15, no. 7, p. e64689, Jul. 2024.

[4] P. Racine et al., “Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis,” JAMA Pediatrics, vol. 175, no. 11, pp. 1142–1150, Nov. 2021.

[5] T. K. Chawla et al., “Prevalence of anxiety symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic among Indian adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Journal of Education and Health Promotion, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 332, Oct. 2023.

[6] L. R. Fortuna et al., “The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety disorders in youth: Coping with stress, worry, and recovering from a pandemic,” Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 531–542, Jul. 2023.

[7] S. Pujol et al., “The relationship between screen time and mental health in young people: A systematic review of longitudinal studies,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 155, p. 108204, Jun. 2024.

[8] J. Knoll et al., “Longitudinal evidence for a vicious cycle of depression and screen time during adolescence,” Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 947–957, Sep. 2023.

[9] S. Madigan et al., “Changes in depression and anxiety among children and adolescents from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” JAMA Pediatrics, May 2023.

[10] A. Diaz-de-Leon-Ortega et al., “Dynamic connectivity between developmentally sensitive limbic regions serving verbal working memory emerges during adolescence,” Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 68, p. 101429, Aug. 2024.

[11] M. K. Haller et al., “Annual Research Review: A developmental systems approach to understanding early life stress and the brain—the importance of context,” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 537–554, Apr. 2024.

[12] Q. Ding et al., “Brain network integration underpins differential susceptibility of adolescent anxiety,” Psychological Medicine, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 193–202, Jan. 2024.

[13] T. Sanders et al., “The effect of screen media exposure on outcomes in 4013 children: Evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children,” Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 211, no. 11, pp. 519–524, Nov. 2019.

[14] M. Hoare et al., “Screen time and screen time reduction for improving health and well-being in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMJ, vol. 1, 2016.

[15] S. K. Muppalla et al., “Effects of excessive screen time on child development: An updated review and strategies for clinical practice,” Cureus, vol. 15, no. 6, p. e40608, Jun. 2023.

[16] M. A. Ironside et al., “Alterations in cerebral resting state functional connectivity associated with social anxiety disorder and early life stress,” Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, vol. 330, p. 111615, Jan. 2023.

[17] A. S. Haller et al., “Increased functional connectivity in the Salience and Default Mode Networks in adolescents with social anxiety disorder,” PLoS ONE, vol. 15, no. 4, p. e0231936, Apr. 2020.

[18] F.-E. Beckmann, H. Gruber, S. Seidenbacher, S. Schirmer, C. Metzger, L. Tozzi, and T. Frodl, “Specific alterations of resting-state functional connectivity in the triple network related to comorbid anxiety in major depressive disorder,” European Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 59, no. 7, pp. 1819–1832, Jan. 2024.

[19] A. Tsamakis et al., “Functional connectivity in youth with generalized anxiety disorder and its association with chronic stress,” Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 193–204, May 2022.

[20] H. Beer et al., “‘Isolation deletes hyper-connectivity’? The association between adolescents’ mental health and online behaviours in a large study of school-aged students,” Current Psychology, vol. 44, pp. 7124–7137, 2025.

[21] M. Oswald et al., “Risk assessment of media misuse or media addiction in children with mental health problems and the effects on brain function,” Archives of Public Health, vol. 80, no. 1, p. 100, 2022.

[22] G. Cerniglia et al., “Trajectories of internet addiction in adolescence: The role of parental bonding and adolescents’ psychological needs,” PLoS ONE, vol. 18, no. 8, p. e0288451, 2023.

[23] J. H. Nagata et al., “Screen time and mental health: A prospective analysis of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study,” BMC Public Health, vol. 24, p. 2088, Oct. 2024.

[24] A. Asanov et al., “Comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of resting-state fMRI in anxiety disorders: Data sharing by cross-sectional studies,” PLoS ONE, vol. 18, no. 8, p. e0288386, Aug. 2023.

[25] L. M. Schmaal et al., “Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group,” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 900–909, 2017.

[26] A. K. Roy et al., “Intrinsic functional connectivity of amygdala-based networks in adolescent generalized anxiety disorder,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 290–299.e2, Mar. 2013.

[27] T. Bajpala et al., “Structural and functional brain connectivity patterns associated with trait anxiety in adolescence,” Neuroscience Reports, vol. 15, pp. 12–24, Feb. 2024.

[31] J. R. Strittmatter et al., “Screen media use and brain development during adolescence: Pitfalls and opportunities for assessing an emergent field,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 164, p. 105800, 2024.

[32] T. K. Oswald et al., “Psychological impacts of ‘screen time’ and ‘green time’ for children and adolescents: A systematic scoping review,” PLoS ONE, vol. 15, no. 9, p. e0237725, Sep. 2020.

[36] M. Paulus et al., “Screen media activity and brain structure in youth: A critical review of mental health and neuroscience findings,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 21, no. 11, p. e12723, Nov. 2019.

[37] M. Maza et al., “Association of habitual engagement in screen-based sedentary behavior with executive dysfunction in adolescents with overweight or obesity,” JAMA Network Open, vol. 6, no. 7, p. e2323231, Jul. 2023.

[38] J. Schmidt-Persson et al., “Screen media use and mental health of children and adolescents,” JAMA Network Open, vol. 7, no. 7, p. e2421981, Jul. 2024.

[46] I. E. Thorisdottir et al., “Active and Passive Social Media Use and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depressed Mood Among Icelandic Adolescents,” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 535–542, Aug. 2019.

[47] A. M. Ivie et al., “A meta-analysis of the association between adolescent social media use and depressive symptoms,” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 275, pp. 165–174, 2020.

[49] C. M. Sylvester and D. S. Pine, “Functional network dysfunction in anxiety and anxiety disorders,” Trends in Neurosciences, vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 527–535, Sep. 2012.

[50] E. A. Hoge et al., “The role of anxiety sensitivity in emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and depression: A meta-analysis of emotional processing studies,” Journal of Anxiety Disorders, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2013.

[51] P. W. Drummond et al., “Dopaminergic and prefrontal abnormalities in adolescent social anxiety disorder in the context of addiction vulnerability,” European Psychiatry, vol. 44, pp. 113–121, Jul. 2017.

[52] L. Wang et al., “Altered default mode, fronto-parietal and salience networks in adolescents with Internet addiction,” Addictive Behaviors, vol. 70, pp. 1–6, Jul. 2017.

[53] K. Subrahmanyam and P. Greenfield, “Altered functional brain networks in problematic smartphone and social media use: resting-state fMRI study,” Brain Structure and Function, vol. 223, no. 9, pp. 4039–4053, 2018.

[54] E. M. Dempsey et al., “Alterations in default-mode network connectivity may be influenced by factors other than Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” Brain Connectivity, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 264–271, Oct. 2012.

[55] Y.-Y. Chen et al., “Negative impact of daily screen use on inhibitory control network in preadolescence: A two-year follow-up study,” Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 60, p. 101218, Apr. 2023.

[56] C. R. Ellis et al., “Video screen time increases amygdala-diencephalon prefrontal coupling: A mechanism for maintaining an anxious state in youth,” Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 67, p. 101387, Jun. 2024.

Published on Mind & Medicine

Leave a comment